By Caroline Baker

December 10, 2023

This past summer thousands of Los Angelenos took to the streets to protest unfair working conditions and fight for union representation. But how did this historically anti-union city get here?

Edward Diaz juggles two part-time jobs at the W Hotel in Los Angeles and the Delphin hotel in Santa Monica. As a cook, Diaz is given the responsibility of feeding hundreds of hotel guests every day, working long shifts in a sweltering kitchen, while being paid minimum wage.

During the pandemic, Diaz experienced a rapid increase in the amount of work given to him at both jobs. Employees were let go as hotels across the country felt the effects of travel restrictions, which meant workers like Diaz had to pick up the slack, with no increase in pay. “They fired a lot of my coworkers,” he said. “And when restrictions were lifted, they hired less than there were before… and I have to do even more work because now people have started traveling again.”

Diaz’s story is one of many. Millions of workers across the country were forced to tighten their belts as the status of their jobs became increasingly precarious. Jobs were lost, wages were cut, and many Americans lost access to essential benefits. But as working-class Americans cut coupons and reused diapers, the world’s ten richest men more than doubled their income.

The pandemic revealed just how wide the wealth gap is between the have and the have nots. According to a 2023 Statistica report, 69% of the total wealth in the United States is owned by the top ten percent of earners. This led people to question why they would continue to put up with long hours and unsafe working conditions while their wages continue to fall or stay stagnant. “It exposed how little the owners, and the bosses actually care about their employees,” said Diaz. “It’s easy for them to just hire one person to do the job of two or three others and then just pocket the rest of the money for themselves.”

In response, like many blue-collar workers before them, people turned to their unions for support. In Diaz’s case, this meant working with the UNITE HERE local 11 union here in Los Angeles. Representing over 30,000 people all throughout Southern California and Arizona, UNITE HERE 11 works with predominantly women and people of color employed in hotels, restaurants, airports, sports arenas, and convention centers. This past summer, UNITE HERE local 11 staged thousands of protests, strikes, and walkouts. With over a hundred contracts expiring at the end of 2023, they have become uniquely situated to fight for improved working conditions, pay, and work life balance.

UNITE HERE local 11 is far from the only union that participated in the “hot labor” summer felt across the country. Over 300,000 workers went on strike this summer, 100,000 of which were in the Los Angeles area. In fact, LA became such a hotbed for labor strikes that, according to a Cornell University Tracker, of the 226 strikes started in the United States this year, 1 in 4 of them began in Los Angeles. From actors to government employees (and everyone in-between), Angelenos from all demographics fought, and continue to fight, for healthcare rights, better wages, AI regulation, and much more.

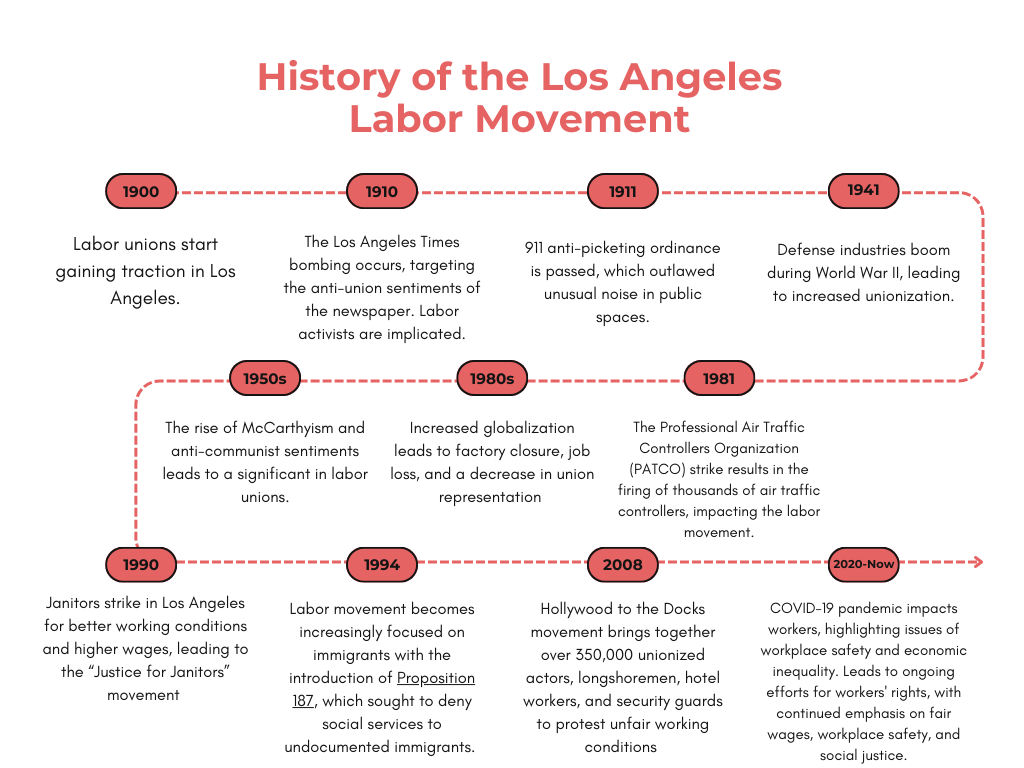

But LA wasn’t always a union town. In fact, for much of its early years, elites in LA saw unions as public enemy #1. Nicknamed “The Citadel of the Open Shop”, LA was known to be vehemently opposed to the labor movement, attracting major corporations with cheap labor and anti-union laws. One such example occurred when Los Angeles City Council passed the 1911 anti-picketing ordinance, which outlawed unusual noise in public spaces.

However, it wasn’t just the politicians that opposed labor activists at the time. The LA times, led by Harrison Gray Otis, published article after article of anti-union propaganda, and played a major part in the passing of the anti-picketing ordinance. The publications garnered an unprecedented amount of attention from the most radical wing of the labor movement, setting the stage for the 1910 bombing of the LA Times building.

Killing 21 and injuring numerous others, brothers James and John McNamara were eventually arrested and charged with the crime. Having been heavily connected to the labor movement, activists were shocked at their arrest. The brothers received wide support from both the movement and the leader of the American Federation of Labor at the time, Samuel Gompers, who believed the brothers had been framed. With this connection to labor activists, the incident not only resulted in the 1911 ordinance, but additionally set back the labor movement in Los Angeles for decades to come.

Beyond gaining almost no traction in early Los Angeles, the labor movements that did exist only supported the rights of certain groups. “The creation of unions was not progressive,” said Jazmin Rivera, Community Education Specialist at the UCLA Labor Center. “They failed to support all types of people and were focused predominantly on white middle-class men.”

Rivera works with primarily young people to spread knowledge of why unions are important and how to join. “I am hopeful for this next generation of workers,” she said in an interview. “50 years ago almost 1/3 of all workers were unionized…[now] only 6% of private sector jobs are unionized.”

Rivera’s comments further hint at the broader anti-union sentiments that have characterized the United States work force since the 1980s. Since then, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the percentage of unionized workers in America has steadily declined. In 1983, 20.1% of wage and salary workers were union members, falling to 15.7% in 1993, and decades later in 2021 to just 10.3%. Companies, and politicians, all across the country took part in what is called union busting, which are various actions taken by politicians and management within corporations to prevent union formation.

One of the biggest acts of union busting came from former president Ronald Reagan in August of 1981. After 13,000 members of the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO), one of the only unions that supported Regan during his 1980 campaign, walked off the job, Regan threatened to fire every member. Protesting for better working conditions and better pay, Regan ended up firing 11,345 government employees and barred them from ever working for the government again.

Beyond specific instances of union busting, increased globalization and the outsourcing of manufacturing jobs to countries abroad additionally resulted in the degradation of unions. Globalization began to increase in the 80s, resulting in mass unemployment and factory shutdowns. “Unions became synonymous with eventual job loss,” said Caroline Luce, a UCLA professor and historian for the UCLA Institute for Research on Labor and Employment. “When unions would form, companies would simply shut down the plant and relocate abroad where labor was cheaper and less regulated.” These moves severely limited the ability of workers to negotiate with their employers for better contracts and working conditions. The jobs that did stay in the United States offered less pay and longer hours as employers began to recognize the desperation in the American workforce with unemployment rising and jobs decreasing.

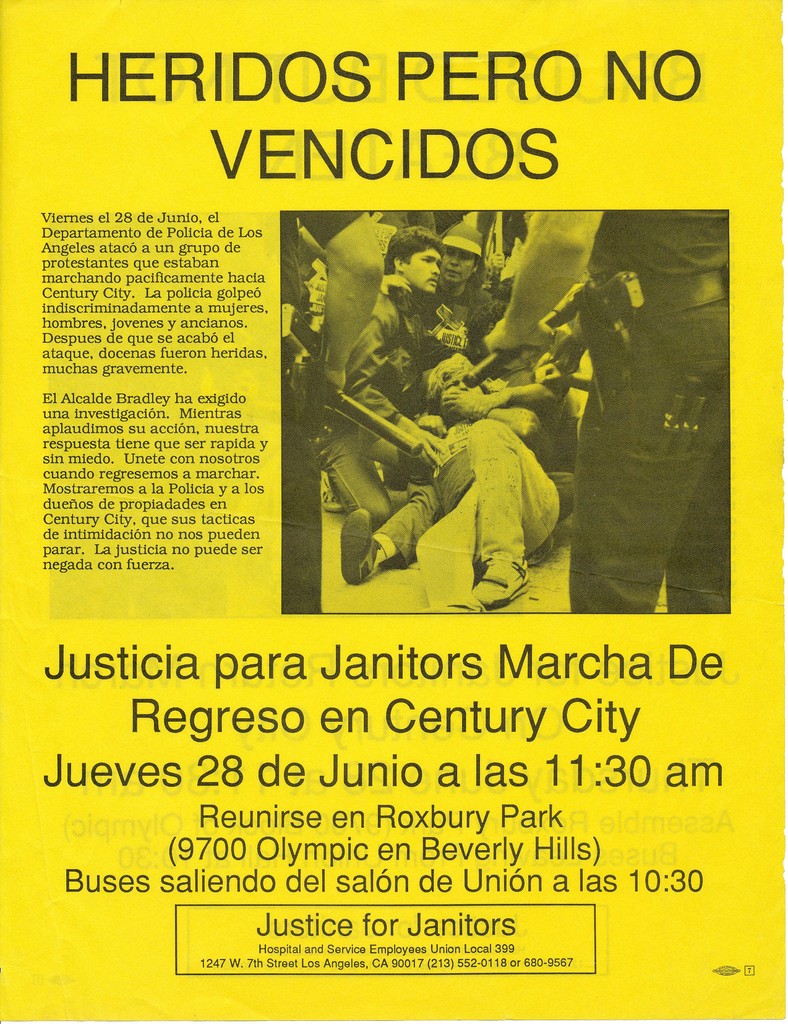

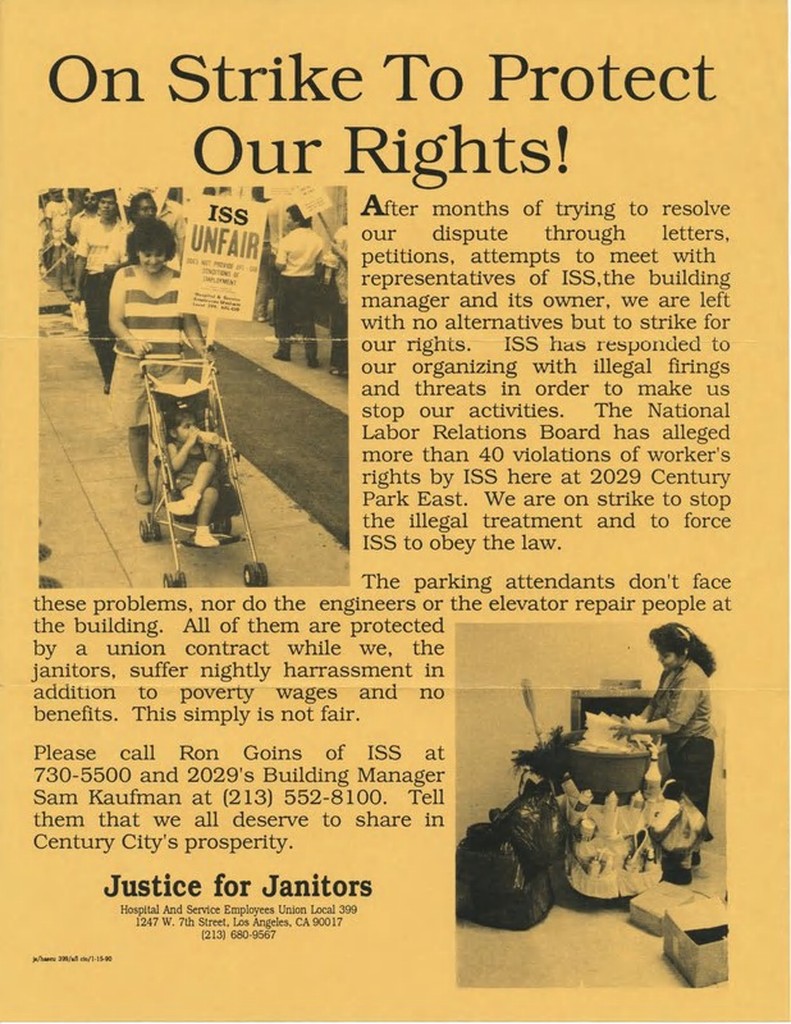

Labor movements would not gain significant traction until the early 90s with the Justice for Janitors campaign. A countrywide movement, with its roots in Los Angeles, leaders Maria Durazo and her husband Miguel Conteras sought to unionize primarily immigrant custodial workers. “This [protest] marked a change in who was represented in unions,” said Rivera. “Because the movement was focused on immigrant workers…the type of people that were allowed to benefit from union work greatly expanded.”

movement

The movement in Los Angeles became increasingly immigrant focused in 1994 with the introduction of Proposition 187, which sought to deny social services to undocumented immigrants, and again in 2008 with the Hollywood to the Docks movement. A massive march where over 350,000 unionized workers protested unfair working conditions, the Hollywood to the Docks movement brought together actors, longshoremen, hotel workers, and security guards before their contract renewal at the end of that year.

However, while Los Angeles saw an increase in pro-union activity, states with Republican majorities did not follow suit. Unions continued to be attacked at the federal level with the 2018 Janus v. American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) Supreme Court Case. “Essentially, what [Janus v. AFSCME] did, was make ‘right to work’ states constitutional,” said Luce. “It means that people [living in these states] don’t have to pay union fees, or join the union at all for that matter, in order to benefit from union negotiations.” Of the 26 states with right to work laws, 23 voted Republican in the 2020 presidential election.

If there are so many actions taken against labor activists, what then accounts for the recent increase in union formation? From Starbucks stores to strip clubs, the activity of unions has increased dramatically. Like Diaz, Rivera oftentimes finds herself using the pandemic to explain the uptick. “It’s hard to imagine that the pandemic doesn’t have something to do with this,” said Rivera. “We all experienced a severe disruption, a disorientation. A lot of workers talk frequently about the cavalier disregard their employers had for them, being willing to send them to risk their lives and not protect them.”

Beyond the pandemic, other deeper factors associated with social justice in general can account for the increased activity. The housing crisis in Los Angeles, for example, has barred minimum wage employees from living and working in the same vicinity. Luce additionally associates the movement with other social movements. “The uprising in the wake of George Floyd’s murder certainly inspired an unwillingness to accept the status quo that isn’t working for people,” Luce said. “Also the climate crisis that we are living through, I think people feel a real sense that there is no future, that there is nothing out there on the horizon for them to look forward to, and given that our government is so stuck, the workplace becomes one little terrain that you can actually feel that you can have an impact.”

This potential for control motivated many workers to seek out union membership. One such example is found in Roger Oda, a longtime member of the Animation Guild and an art director for Marvel Animation. “The real goal of unions is industrial democracy,” said Oda. “It’s about bringing the processes and procedures of our democratic governance into our workplaces.” Oda serves on the executive board of the Animation Guild, known as Local 839 of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE), which represents over 6,000 artists, technicians, writers, and production workers in the animation industry. “My union provides me with a healthcare plan and helps ensure that our wages and hours are humane,” he said. “In an industry as taxing as animation, many of my friends and past coworkers have been overworked and underpaid, and the Animation Guild helps fight against this.”

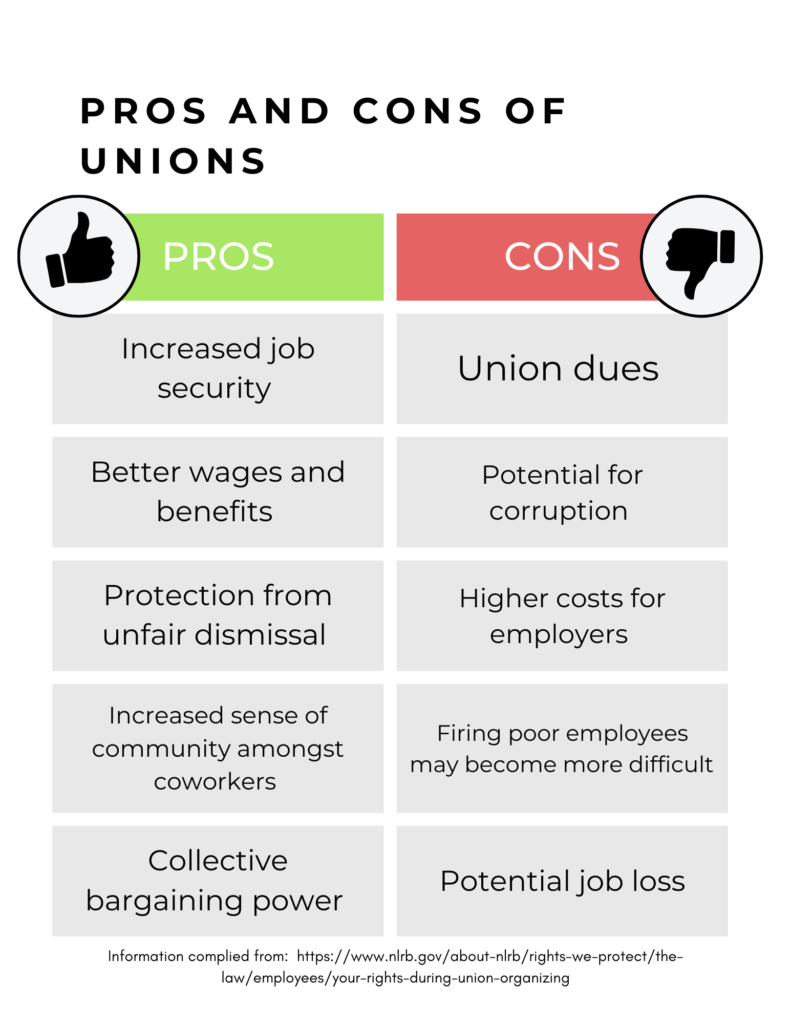

Oda has listed some of the key potential benefits that come with joining a union,which are healthcare and contract bargaining assistance. On their website, the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), lists countless others, such as family friendly work environments, time of to care for family, paid time off, student loan repayment, scholarships, job training programs, and an updated wage system to keep up with the growing cost of living.

Unfortunately, as Luce warns, the quality of a union is only as good as its leadership. “There are many cases wherein workplaces are unionized but they are not effective because they fail to implement a democratic system within their union,” she said. “[For example] the UAW union was so deeply corrupted for so long that they have been ineffective for most of their existence.” Luce is alluding to the long history of embezzlement found in the United Auto Workers union, where millions of union dues were used for the personal gain of its leaders. For many Americans, this UAE case is a strong argument against union membership. “Examples like this ruin public perception of what unions actually are,” said Luce. “It hurts the overall argument for unions and why they are important and leads to the union busting that we see today.” The infographics below depicts some additional pros and cons of joining a union.

Despite this, American approval of unions has reached levels not seen since the ‘60s. According to a 2022 Gallup report, 71% of Americans now approve of labor unions and their action, indicating that strikes like the ones in Los Angeles, will continue to be impactful. Additional support has been seen on the federal and international level as well. Back in September, President Joe Biden made history when he joined a picket line in Michigan to show support for protesting autoworkers, making him the first U.S. president to do so. The UNITE HERE Local 11 protests have caught the attention of international sports star Lionel Messi. After hearing about the strikes, he refused to cross picket lines and canceled his stay at the Fairmont Miramar in Santa Monica.

However, these strikes are only the first steps in a long journey towards improved labor rights. “We have to keep in mind that the system is still very stacked against workers,” said Luce. “I think there is undeniably a broader enthusiasm [for] public support for unions and public support… but there are real structural obstacles to [forming] a union.”

Rivera pointed to differences found in the workplace which make it difficult to just start a union. “It really depends on who is working in that store”, she said. “There’s a huge difference between a store filled with college students who are working part time, and one where the people there have been working there for ten plus years.”

Rivera is correct when she said starting a union can put jobs at risk. Although the National Relations Labor Board holds that it is illegal to fire, demote, or penalize workers for forming unions or engaging in activities, the penalties are low. Even when employees take legal action, companies claim other reasons for their termination, such as being one minute late to a shift.

Many companies still use union busting techniques to dissuade non-union employees from joining. According to a 2019 report from the Economic Policy Institute employers spend more than $300 million a year on union busting. From coercing employees into proliferating anti-union rhetoric to coworkers, to company-wide anti-union meetings, these tactics can be highly effective. “Big corporations like Amazon and Starbucks have lots of money to bust unions and discourage union activity,” said Rivera. “There are so many ways that these big companies instill fear into their employees and that is a real challenge for us when trying to mobilize workers.”

Even without the threat of fire, unionizing is a long and arduous process, one in which not a lot of people are educated on. According to a 2019 MIT report, only one in 10 non-union employees would know how to start one, should they want to. Those who do want to start one must then convince more than half of their coworkers to vote in favor of said union and during union elections, which cannot be done on company property or during work hours. Once this is completed, negotiations are then carried out between the union and the employer to create a collective bargaining agreement (CBA).

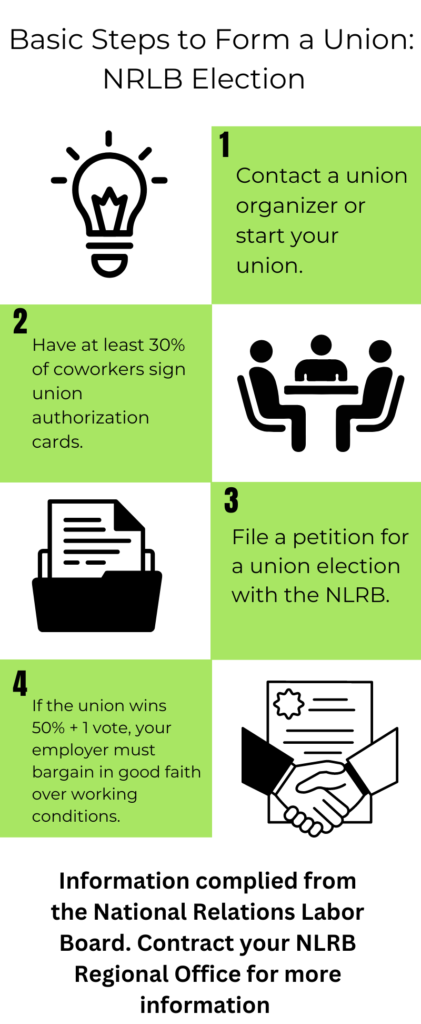

The last step is the most difficult. While there has been an increase in union activity and union elections, there has been a serious lack of actual union contracts. This is what some labor activists call a “soft” form of resistance. “Companies will sometimes wait over a year to participate in negotiations,” said Luce. “At that point the union could lose its certification and have to start the process over again.” he infographics below depict the steps taken to start a union. The National Relations Labor Board offers two ways to form a union depending whether or not your employer voluntarily recognizes the union.

Nevertheless, people are still enthusiastic about the future of unions. There is a new generation of activists who are learning from the protests. “Young people are going to learn so much from this past summer that’s going to influence the next strike and the next labor movement,” said Rivera. “And at the same time [the UCLA Labor Center] is teaching young people how to interact with and join unions.” Futhermore, this is not the first time specifcally UNITE HERE local 11 has gone on strike and won. The video below is footage of protesters celebrating their sucessful contract renegotiation in 2005.

Protesters like Diaz and successful contract renegotiations won recently by the Writers Guild of America, illustrates the perseverance of labor activists.“There have already been positive outcomes of our protesting,” said Diaz. “Messi is a huge star and for him to support us shows our success.”